By Arnold Zable

This article first appeared in The Well.

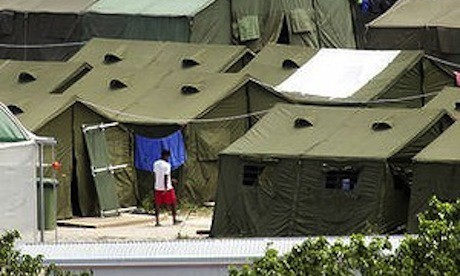

The suffering of asylum seekers currently in detention on Nauru and Manus Island is unbearable. Imagine it, to be living in tents, in the heat and rain, on isolated islands, with years of waiting ahead, in limbo, and with the knowledge that for many Australians out of sight means out of mind. How has it come to this? There are reasons, but first, before the politics, a few stories – stories that indicate what our political leaders should be saying; stories that provide inclusive vision of who we are.

In February 1847, a journalist travelling through Ireland noticed that some of the people’s lips were green. Their lips were green because there they were eating grass. And they were eating grass because there was little else to eat. It was a time of mass starvation that became known as the Great Famine.

Out of a population of 8 million, one million died. And out of the remaining seven million, one and a half million took to boats. Some fetched up on the shores of America, and others found their way to distant Australia. In all, over three million people left Ireland between 1845 and 1870.

The largest Diaspora in modern history comprised the 15 million people who forsook the British Isles in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Many left due to ruthless land clearances and an agrarian revolution that saw millions driven from their farmlands. Then, as now, there were some who perished when their boats sank on the high seas. Then, as now, such tragedies did not deter people from risking the voyage. Quite a number came to Australia. In other words, we are, except for indigenous peoples, a nation of boat people. That is the inclusive tale of who we are.

Voyage of the Damned

In 1946, the Melbourne publishing house, Dolphin Books, produced an English translation, of the novel Between Sky and Sea, originally written in Yiddish by Herz Bergner. The novel depicts the voyage of a group of traumatised Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s terror. The Greek freighter has been at sea for weeks, drifting helplessly, en route to Australia.

Born in the Polish town of Radimno in 1907, Bergner’s family settled in Vienna during World War I before returning to Poland. During the inter-war years, Bergner lived in Warsaw, the hub of Yiddish cultural life in Eastern Europe. His first collection of short stories Houses and Streets was published in 1935. The young Bergner served his writing apprenticeship when Yiddish literature was at its creative zenith.

Yet it was also a time of mass poverty and political turmoil. The storm clouds of war were gathering. Bergner seized the opportunity to emigrate. He settled in Melbourne in 1938 where there was an active community of Jews who maintained Yiddish as their mother tongue. As it turned out, he was one of the fortunate ones, able to get out just in time. In 1941 he published The New House, a collection of short stories reflecting Bergner’s experiences and those of his immigrant readers, their recent journeys and the challenges of adapting to a new life.

Between Sky and Sea was one of the earliest responses to the dire fate facing Jewish communities in Europe. The writing is propelled by a sense of urgency. He wrote it while news was filtering through that a catastrophe was taking place. His people were being enslaved and murdered, or forced into flight. In January 1942, Bergner had published an essay pleading the case for increased European migration to Australia. Once flourishing Jewish communities, he wrote, were being wiped from the face of the earth.

Bergner would have known of the ill-fated voyage of the St Louis, the ocean liner that left Germany in May 1939 with over 900 Jewish asylum seekers on board fleeing the Third Reich. The ship was turned back from Cuba and not permitted to land in the USA and Canada. The refusals prompted several passengers to attempt suicide. As the ship sailed back to Europe, a group of passengers took over the bridge and occupied it until their rebellion was put down. Through intense negotiation and the support of the empathetic captain, Gustav Schroeder, the passengers were able to disembark in Antwerp before the ship returned to Germany. Nevertheless, 254 of the passengers perished in the Holocaust.

The refugees on Bergner’s fictional Greek freighter undertake their voyage several years later while the war rages. They are trapped between sky and sea, and within the terrors of their recent past. They have lost entire families and witnessed the destruction of their communities. They have wandered through many lands and are tortured with guilt at having been spared the fate of those left behind.

With each day at sea they edge closer to despair. Their meagre rations of food decrease. Those who succumb to disease are buried at sea. The passengers no longer know where they are. They are an unwanted people and endure racist taunts from some of the crew. When typhus breaks out on board, a seaman hisses: ‘Human beings? Important people? You have been thrown out of everywhere and no one will take you in. All doors and gates are closed to you. We can’t put in at any port because of you. Everybody is afraid you’ll get your feet in and never go away.’ The sea is a malevolent force, the sun an inferno, the boat a mobile internment camp. It is a voyage of the damned.

Life in Limbo

Between Sky and Sea remains as relevant today as it was when it was first published. There are millions on the move in search of refuge from oppression. Many languish in camps for years on end, while others are en route, prepared to risk all to gain landfall on firmer shores. Theirs are perilous journeys enacted anew in each age. Some make it and some don’t.

Fast forward to 19 October 2001, when a leaky fishing boat sank at 3.10 in the afternoon, en route to Australia. The exact time is known because watches stopped. 353 men, women and children fleeing Iraq and Afghanistan drowned. There were forty-five survivors. Bergner’s account of the fate of the passengers on board the Greek freighter is chillingly similar to survivors’ descriptions of the SIEVX sinking. The two disasters, sixty years apart, one imagined, the other real, encapsulate the universal plight of asylum seekers. They highlight the fraught nature of the journey, and the desperate measures that people take to escape oppression.

The sinking of the SIEVX was the biggest post-war maritime disaster off Australian waters. At the time of the sinking the Howard Government was advising its navy personnel to force asylum seeker boats back out to sea. Like Bergner’s characters they were consigned to live in limbo, their goal so tantalisingly close, yet agonisingly out of reach.

I came to know the three survivors that settled in Melbourne. Iraqi asylum seeker, Amal Basry survived by clinging to a corpse for over twenty hours. She became much loved as a passionate witness to the event. When she finally received her permanent resident’s visa she said ‘I am a free woman in a free country.’ In a cruel irony she died of cancer in 2006, but her story and the impact of her courage lives on.

This is just one of countless stories I have heard in recent years. I have walked with distraught asylum seekers through sleepless nights, as they yearned for the day that they would be reunited with their loved ones. I have heard their tales in detention centres, at community centres, and in kitchens and living rooms throughout Melbourne.

Arm Yourself With Stories

There are saving graces. The most powerful I know is the work being done by the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre now based in West Melbourne. Since its foundation in 2002, by its CEO Kon Karapanagiotidis, the centre has welcomed over 8000 asylum seekers. It is currently helping over 1200 asylum seekers who have been released into community detention, on bridging visas. If it were not for the work of the Centre, its staff and 800 volunteers – with a range of many services including legal aid, medical aid, English lessons, and a community centre where they can spend time during the day – these asylum seekers would be isolated and destitute. And what is their ‘crime’? Doing for themselves and their families, what we would have done in their shoes, and what our own parents or grandparents did in the recent past.

So how has it come to this, to such heartless policies, and to the breaking of UN conventions that deem it a basic human right to seek asylum from persecution? I believe it can be traced back to mid 2001, to the Tampa affair, and to the Howard Government’s response to the boat people crisis. Howard broke the tradition of bi-partisanship on refugee issues fostered during the Fraser-Whitlam years, and used the boat people issue for political gain.

Asylum seekers became political footballs. The race to the bottom was set in motion. No matter how cruel you can be, I can be crueler became the name of the game, supported by polling that confirmed the political advantages. This is the current song being sung in Canberra.

What can we do? Contact the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, donate or volunteer. Better still, come to the centre and meet asylum seekers face to face – and you will see a mirror reflection of your forbears. And you will go away armed with stories that you can tell to your friends, spread through your networks, bring up at dinner parties, to counter the demonization of people who have done what millions have done before them – had the courage to seek a new life, free of persecution.

Rosh Hashana Newsletter – Green Lips