An uncontroversial question: Should Zionist Synagogues join their local Zionist Council?

[This article appeared under a slightly different heading in the Australian Jewish News this week]

Harold Zwier 15th February 2013

Recently, a small modern Orthodox Synagogue in East St Kilda, decided to join the Zionist Council of Victoria. Our Synagogue is a warm and friendly kehilla composed of interesting people. The Synagogue Board thought the decision to join the Zionist council was completely uncontroversial and justified their decision as “an appropriate action for our shul to take”.

And indeed why should there be a question? Our Synagogue has always described itself as a Zionist Synagogue. Item 9 of its Statement of Purposes aims to “foster the commitment and attachment of its members to the State of Israel”. We say a prayer for the welfare of the State of Israel every Shabbat. Return of the Jewish nation from exile is a central motif of Judaism and Israel is so central to modern Orthodoxy that joining the Zionist council seems, at first blush, to be no more than crossing the t, or at least dotting the i on our commitment.

Nevertheless, I believe that our Synagogue should not join the Zionist council without applying a level of critical thought to this issue, in line with the general intellectual engagement encouraged by modern Orthodoxy.

It is not the bond between Israel and modern orthodoxy that is in question, but the differences between our secular and religious engagement with Israel – and to what extent there is common ground between the two.

So, what is the contrast?

Modern Zionism is a product of ideas developed in the last couple of centuries, emanating from the Enlightenment. Orthodox Judaism’s attachment to Israel has a history spanning three millennia. Of course modern Zionism has its roots in religious Judaism, but the nationalist and political agenda of modern Zionism is historically based and secular. When religious groups in the diaspora participate in political/national activities relating to modern Israel, they are essentially participating in a secular process.

In the barrage of material about Israel in the media and beyond, the lines between the religious and secular often blur. But Orthodox Judaism has not embraced the view that the modern state of Israel is the fulfillment of Gd’s promise to return the Jews from exile.

Firstly, the Yom Tov Mussaf amidah includes the prayer, “U’mifnei cha’ta’ainu galinu mai’artzeinu . . .”, “But because of our sins we have been exiled from our land. . .”. These prayers have not been altered or abandoned as a result of Israel’s creation in 1948. Indeed, modern Israel is a secular state – not a halachic state (thank Gd).

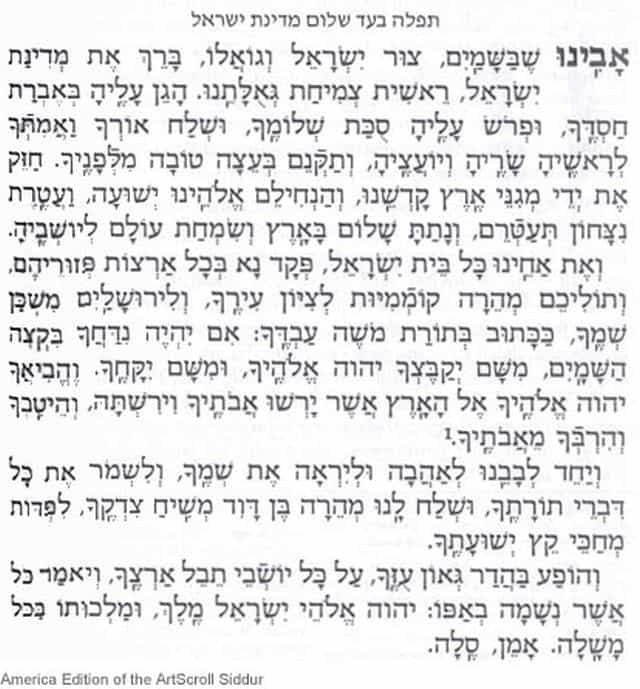

Secondly, support for saying the prayer for the welfare of the state of Israel can be found in Pirkei Avot 3:2, “Pray for the welfare of the government”. We say a prayer for the welfare of the country in which we live and Israel – both countries we care about. The prayer for Israel includes “. . . ba’reich et m’dinat yisrael, reisheit tzmichat g’ulateinu”, “. . . bless the state of Israel, the first flowering of our redemption”. Not everyone in orthodox Judaism accepts those words. One strongly Zionist member of our Synagogue said “I make the mental caveat that dissents from ‘reisheit ..ge’ulatheinu’. I do not locate a messiah in a political entity”.

Thirdly, the prayer for the welfare of the state of Israel is not recited in all orthodox Synagogues. Few, if any orthodox Jews would regard those Synagogues as being any less authentically Jewish by their choice not to say that prayer, or indeed a choice not to align with Zionism at all.

Given these quite significant differences between religious and secular approaches to Israel, the decision to join the Zionist council can be understood in one of two ways.

If the decision follows from the belief that the state of Israel is indeed the beginning of our redemption from exile, then the Zionist council might be seen as embracing both secular and religious forms of Zionism. Joining the Zionist council is a logical step from that perspective. Of course while this may express the views of some in our Synagogue, it may alienate others. It is a position that narrows the way in which the Synagogue fosters “the commitment and attachment of its members to the State of Israel”.

But if the decision follows from a blurring between the secular and religious, then it is problematic in a different way. Joining the Zionist council requires adoption of the “Jerusalem Program 2004” into the Statement of Purposes of our Synagogue. This is a statement of the nationalist, political and cultural principles of Zionism. Adopting it moves our Synagogue away from an inclusive religious engagement with Israel, into a much more specific secular, politically aligned and nationalist engagement with Israel.

As the Synagogue member quoted previously put it:

“i am a Zionist i am a member of this shule i join a shule to be part of a congregation i’ll join the Zionist council if I want to formalize my zionist status i don’t want my shule to do that for me”

This shift – this realignment – of our Synagogue is much more profound than might be first thought. Within the philosophical and religious boundaries of Orthodox Judaism, the intrusion of nationalist, secular and political interests works directly against the principal aim of nurturing an inclusive religious community. Since the decision to join, or not join the Zionist council makes no material difference to the longstanding openly expressed commitment of our Synagogue to Israel, the question falls back on the Board to articulate a significant purpose and benefit for this change.

Harold Zwier is a former Board member of his Synagogue and a member of the Zionist council through another organisation.

An uncontroversial question: Should Zionist Synagogues join their local Zionist Council?