Yael Winikoff is the AJDS community organiser.

This year marks 70 years since Israel became a fledgling nation-state. In our communities we have seen celebrations marking Israel’s 70 years, and commemorations of 70 years since the Nakba. And challenging conversations in between.

This year I noticed that the term Nakba is most commonly prefaced with “to Palestinians, the Nakba is…” This got me thinking. Does the Nakba only hold this meaning and significance to Palestinians? Is it a narrative that is at odds with non-Palestinians? What does the Nakba mean to those of us who aren’t Palestinian? What does it mean to those of us who are Jewish? And why are some Jews in Australia so uncomfortable with this word?

Let’s begin by framing what the nakba is.

The Nakba, an Arabic word meaning catastrophe, refers to the exodus of some 700,000 Palestinians in 1948. It is commemorated on May 15th every year, a day after Yom Ha’azmaut (Israel’s Independence Day), and the same day that the armies of neighbouring Arab states invaded to take control of the Arab areas of the UN partition plan. But the Nakba is not about May 15. It spans the beginnings of the state of Israel and the dislocation of Palestinians from their lands and the decimation of Palestinian society in 78% of historic Palestine (what some refer to as ethnic cleansing). It saw 531 Palestinian villages destroyed, and 700,000 Palestinians uprooted from their homes, out of 900,000 from the area that became Israel.

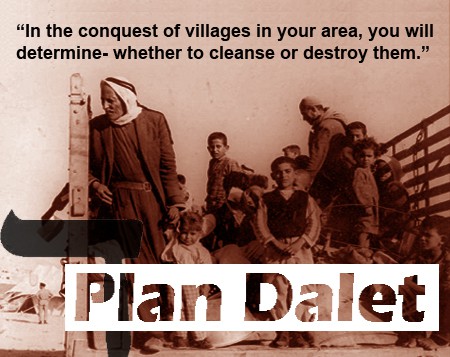

The Nakba is not confined to May 15, because by May 15, 1948, around 250,000 Palestinians had been expelled, or fled. On March 10, 1948, the national Haganah (Jewish paramilitary during British mandate) headquarters approved ‘Plan Dalet.’ This military policy document contains a premeditated intent to expel as many Palestinians as possible from the territory to become the Jewish state. (1) On April 14, 1948, David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first Prime Minister and one of its primary national founders, proclaimed: “From day to day we expand our occupation. We occupy new villages and we have just begun.”

Once upon a time the Israeli narrative of 48 was that most Palestinians left of their own accord. That in fact Palestinian and Arab leaders encouraged Palestinians to leave until their armies could secure all of Palestine from Israel, and they could safely return to their Arab lands. Robin Rothfield in his article for Just Voices quotes the “accepted expert on this subject,” Israeli historian Benny Morris; “The Palestinian refugee problem was born of war, not by design, Jewish or Arab.” In the 1980’s Morris and other ‘new historians’ confirmed what Palestinians have been saying for decades, that the majority of Palestinians left because they were instructed to do so by their leaders is a myth. In most regions, the vast majority of Palestinian exodus was a direct result of Israeli military intervention.

Causes of abandonment of Palestinian villages according to Benny Morris.

|

Decisive causes of abandonment |

|

|

military assault on settlement |

215 |

|

influence of nearby town’s fall |

59 |

|

expulsion by Jewish forces |

53 |

|

fear (of being caught up in fighting) |

48 |

|

whispering campaigns |

15 |

|

abandonment on Arab orders |

6 |

|

unknown |

44 |

David Ben Gurion, 1948: “We must do everything to insure they [the Palestinians] never do return … The old will die and the young will forget.” After 48, Palestinians who had fled their villages were not allowed to return. Even attempting to collect possessions or crops from their fields could be met by IDF open fire. The “Palestinian refugee problem” is a direct result of this policy, a policy which continues to this day. And so, the Nakba continues. The absentee property law, which was passed in 1950 to allow Israel to take control of Palestinian refugee’s houses, still presides and is used today to continue to take control of Palestinian’s properties for Israeli settler expansions. In 2015 the Israeli Supreme court legislated to be able to use this law in East Jerusalem, territory occupied in 67. When we speak of the Nakba, we not only speak about an historical event, we also speak of the ongoing impacts this has had on Palestinians and the region.

Samah Sabawi:

“Nakba is not an isolated incident in history. Not a single memory that stands distant and frozen on the pages of time. Its commemoration is a reminder of the beginning of an ongoing crime. It forces us to reflect on a relentless inescapable reality. We carry it in our collective conscience, a precious pain that cannot be extracted from our identity. We are Palestinians and we cannot forget what has not yet ceased to be.” (2)

There is a section of the Jewish left who oppose the 50-year occupation of the West Bank and Gaza but choose to ignore or deny the relevance of the Nakba. 67 did not occur in a political and historical vacuum. Orly Noy, Israeli writer and journalist writes: “One cannot truly understand the atrocities of the occupation of 1967 without recognizing the catastrophe of the Nakba in 1948.” (3)

Speaking on the 67 occupation, Dr Micaela Sahar says:

“I would say that for Palestinians, while there are material changes created by the Six Day War, and while it is the date at which an idea of Occupation commences, in fact this is a date that forms part of a continuum of processes that crystallise in the creation of the Israeli State in 1948.” (reproduced in Just Voices, 2017)

To Palestinians, the Nakba is the pain of being dispossessed from their land, and the struggle to return to it, and that should matter to all of us. One cannot engage in a truly meaningful way with Palestinian rights and justice without addressing the Nakba. Palestinian political and social activist Abir Kopty writes: “The right of Return is at the core of the Palestinian struggle for liberation. The Nakba .. is what unifies Palestinians; this is where injustice and colonization of Palestine began, not in 1967. The issue of return is a collective issue; the dream of return is present in every Palestinian.”

Why is Israel so afraid of the Nakba?

In 2011 the Israeli Knesset passed an amendment which became known as the “Nakba Law,” authorising the Finance Minister to reduce state funding or support to an institution if it engages in an activity deemed against the state. This includes; “commemorating Independence Day or the day of the establishment of the state as a day of mourning.”(4) The origina

l intention of the bill was to completely criminalise any mentioning of the Nakba, with a punishment of up to three years in prison. (5) What is it about acknowledging the historical account of 48 that is so threatening to Israel and its fervent supporters?

There is an argument that those who commemorate the Nakba espouse the view that the state of Israel should not have been created and/or that it has no right to exist. This year some 50,000 people marched in the streets of Melbourne at the invasion day rally. For those of us who marched, did that mean that Australia should never have been created and it has no right to exist? The point is, this is the wrong question to ask. Acknowledging a communities suffering does not equate to eradicating the existential rights of anyone else. Decolonisation is not about saying Australia, or Israel, never had a right to exist, it is not about travelling back in time to condemn early colonial history and see how much we can reverse. It is about acknowledging the effects of colonial dispossession and actively addressing its ongoing impacts. It is about reparation to Indigenous peoples and affirming their sovereignty. Is Israel avoiding these reparations?

Are we scared that acknowledging a historical account of events in 48 will unravel the false narratives of hostile Palestinians and neighbouring Arabic countries, and in fact give humanity and virtue to the Palestinians whom Israel is vested in dehumanising and demoralising for its ‘security concerns and right to exist?’

For Jews. the Nakba means facing the responsibility for the crimes which have been, and continue to be, committed in our names. It means acknowledging and supporting Palestinians struggle for justice as we hold our own dreams of self-determination and security. It means holding multiple narratives, histories and traumas and pouring truth to tales which have been weaponised for the sake of the State. It is holding Palestinian realities and aspirations with our own rather than eradicating them, and from here, dreaming and forging a future for us all.

- This article appeared in the AJDS Magazine Just Voices 16: Israel / Palestine 1948