Larry Stillman is an academic who trained at Hebrew University and Harvard. He leads a community development project in Bangladesh with Oxfam.

This is an edited version of the original article published in Arena magazine, 2012, Issue #120.

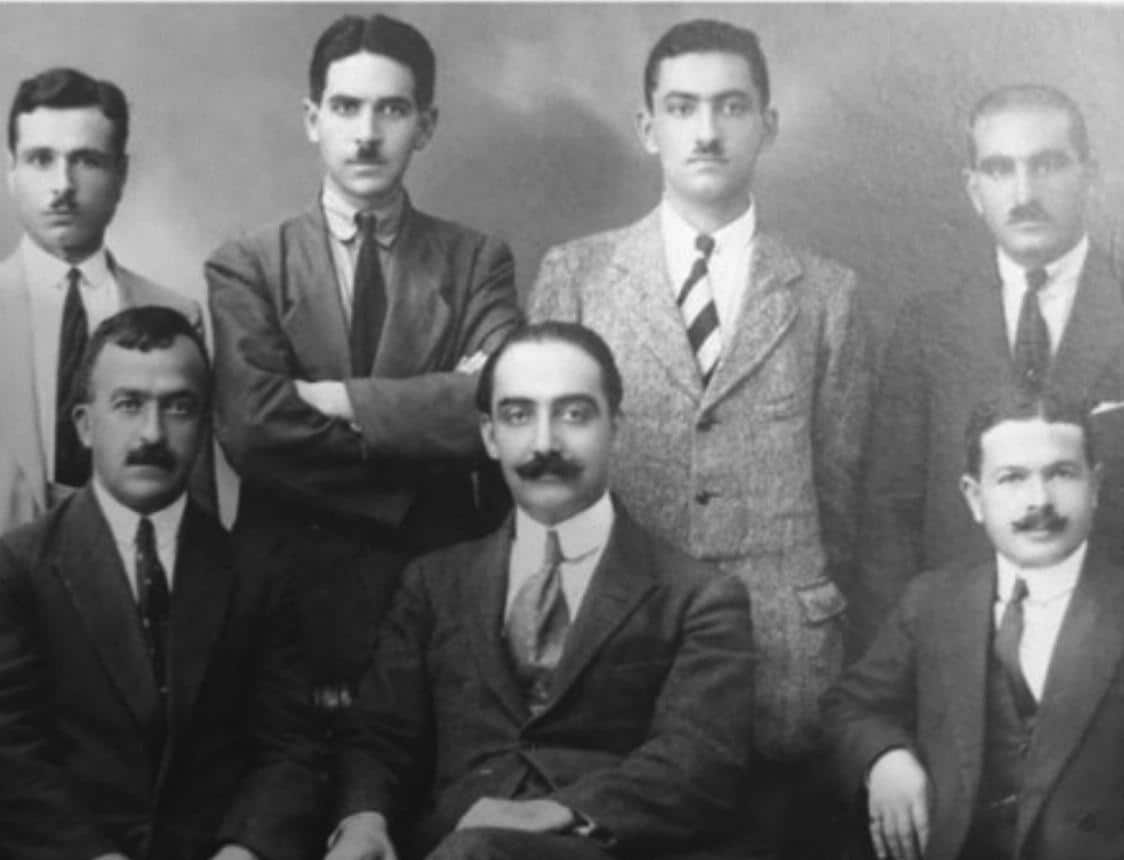

Photo (Above): Private collection. In this photo, George Khamis is standing on the far left, with Khalil Sakanini sitting in front of him. Taken in 1919

This is a story of a now old book and its connections to war, displacement, cultural destruction; the possibilities of an apology and reconciliation; and the remarkable things that connectivity can achieve. The story is about a 1937 copy (in very nice letterpress) of the now wonderfully eclectic and archaic A Dictionary of Modern English Usage by Henry Fowler. It is one of those blue clothbound Oxford University Books that were easy to find years ago.

I bought the book in around 1978 in a second-hand book shop in Jewish West Jerusalem when I was a student. I have been back in Australia for over twenty-two years now. I had never really thought much about the book’s previous owners, of which there were at least two. One owner’s name appears in English on the inside cover as ‘George Khamis’, without a date, accompanied by a number (perhaps a lot number), and the name of the used book shop. On the right-hand page, in Hebrew, it reads ‘from the library of Margalit Anda’.

Ever since my time in Jerusalem as a student in the 1970s, I had questioned the Zionist narrative. I knew that something was wrong in how the history of the city and country was presented, and that there was a myth about equality in the allegedly unified city. At that time, the Occupation was still ‘new’. The hills of Jerusalem were devoid of the plague of settlements that now exist, and it was still a relatively small place. Palestinian neighbourhoods in the eastern part of the city were intact. However, Palestinians appeared to be very much a second-class impoverished group, with whom one had little interaction. Mostly they seemed to be street-sweepers, cleaners or vendors of grapes in the neighbourhood, on whom one could practice bad Arabic. This was no benign occupation. It all seemed quaint and colonial, and plenty of bullet holes remained from 1948 and 1967.

In this environment, I don’t think I ever thought that there had been a vibrant Palestinian middle class. I knew that just down the road from where I was later living in south-east Jerusalem, in an area known as the German Colony, there were many beautiful stone ‘Arab houses’ with Armenian tile work and inscriptions in Arabic.. Closer to my flat were large deco apartment buildings and houses that had been occupied by ‘Arabs’. In the park next to my flat, behind a stone wall, there was the Greek Orthodox Monastery of San Simon, and the neighbourhood below was known as Katamon Some people still used Arabic names to refer to neighbourhoods rather than more recent Hebrew additions. But like so much in Jerusalem, the past was being erased, and there was no indication of who the mysterious prior owners of property in Katamon were. The prevailing ideology was that ‘our national minority’ (Hebrew: mi’ut le’umi) was rural, conservative, undereducated and quaint. The Naqba was not a word used at that time, and in any case, it was considered their fault if they had left their country.

I began to think about my Fowler’s. Who was George Khamis? And who was Margalit Anda? How did the book get to be sold?

In early May 2012, after a few searches on Google, I was amazed to find Khamis mentioned in an account of the intellectual life of late Ottoman and then Mandate Jerusalem until the Naqba. He was part of an active circle of mostly Greek Orthodox Palestinians who lived in the new south-eastern

suburbs of Jerusalem. They gathered around the figure of Khalil Sakakini, who formed the ‘Vagabond Café’ and cultural group. Sakakini and his comrades were also active educators teaching at the Dusturiyyah (Constitutional) school which he founded.

This very bourgeois, cultured and Europeanised way of life was in complete contrast with the life of poorer Palestinians in the Old City or in villages around Jerusalem. Hala Sakakini also mentioned that Khamis entertained her family with records from his large collection of European music.

As well as the documents about Khamis, I also found a photo.

Somewhat inspired by these finds, I started posting my finds on Facebook while looking for more information on the internet. On 28 May 2012, I found another reference to George Khamis that could not be coincidental. I discovered that there was an ongoing project—‘The Great Book Robbery’ <www.thegreatbookrobbery.org>—to identify books which had been collected by the prestigious Jewish National and University Library (National Library) in 1948 and stamped as ‘Alien Property’. Approximately 30,000 books were collected from abandoned Palestinian properties in Jerusalem in the period between May 1948 and February 1949 by librarians and soldiers. However, about 24,000 were disposed of because they were considered irrelevant or hostile material.

The Great Book Robbery project, established with the support of the Dutch-Palestinian MP Arjan El Fassed, aims to put online the entire catalogue of 6000 Alien Property books, with titles translated, as an independent source,

The intellectual prestige of such collections is well known. Jerusalem housed many important private collections, such as that of the Nashashibi family who had been in the area since the fifteenth century. The National Library became increasingly caught up in holding onto, rather than restoring the valuable Alien Property. Initially the National Library had some discomfort at being engaged in such a form of book collection. Even Israeli Palestinians who worked on cataloguing books believe that intentions were originally benign. However, as Gish Amit puts it based on a study of the archived memos and documents from the period:

After a while, no one was willing to seriously discuss returning the books to their owners, who were already far from Jerusalem at that point, until this option had gradually become inconceivable. The people of the National Library did not pre-plan the pillaging; in the course of the war they learned from soldiers about the existence of the books, and they went to take them. Perhaps they sincerely believed they were saving them, and maybe they seriously considered returning them to their owners once the fighting ended. However, they very quickly fell in love with their plunder, and the possibilities which this plunder presented pushed away every other thought from their mind.

It is clear that Palestinian patrimony was considered fair game. A March 1949 memo listed the names of sixty Palestinians whose books had been collected—included amongst them the name of George Khamis.

A blog post by researcher and librarian Hannah Mermelstein on the Great Book Robbery website told the story of one person who gained access with a researcher to the archive

: ‘… the very first book we opened together had the name “George Khamis,” to which my comrade said, “George! Let me tell you about George! He also drank tea every morning with my grandfather and Khalil Sakakini’.

I was stunned. This was a real person, and a connection to someone living, and there were other books that belonged to him. I sent a query, saying that I thought I had a book of Khamis’ as well. Shortly thereafter, I was then sent information by Mona Halaby, an American Palestinian whose family also came from Katamon. She sent me a photo of one of Khamis’ books and from comparing the signatures in the two books, there could be no doubt that I had his Fowler’s.

Now, what do we do this information?

With the Israeli victory in 1948, the post-Naqba period saw an attempt to eradicate where possible Palestinian presence, institutions and memory, whether by stealth, convenience, accident, or hegemonic pressure on bureaucrats like librarians. What happened and is happening in Palestine/Israel is what Baruch Kimmerling called politicide, ‘a gradual but systematic attempt to cause …annihilation as an independent political and social entity’ in a land where two sets of conflicting aspirations and narratives have come into terrible collision. The destruction of Palestinian cultural capital has been aided by the National Library’s activity. I may be unable to restore Palestinians to their homes, but at least they should have their books back.

It seems to me that there is a good example for what should be done. Some of the books I studied with at Hebrew University contained a stamp in German from the Nazi research Division for the Study of the Jewish Question of the Reich Institute of the History of the New Germany (Forschungsabteilung Judenfrage des Institut zur Erforschung der Judenfrage). These books ended up at Hebrew University via the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Fund that was set up specifically to return books stolen from Jewish libraries or to place them in new ‘homes’ after the war.

Mermelstein quotes the 1954 Hague Convention for the Preservation of Cultural Property, Section 3, ‘to return, at the close of hostilities, to the competent authorities of the territory previously occupied, cultural property which is in its territory’. Given that the National Library is a leading cultural institution internationally and the recipient of many books stolen in the Holocaust, it knows the importance of acts of restorative justice.

The steps to be taken are that the books that are now classified as Alien Property be returned to either their rightful owners (if they can be identified) or descendants, and for those items which cannot be identified, to a Palestinian cultural institution of which there are a number in the area, and a formal apology offered.

I realise that many Palestinians and supporters of Palestinian rights may regard such a proposal as a form of whitewashing and legitimisation of unequal relationships. But the outcome may well be positive for Palestinians and something of a watershed event for a major Israeli cultural institution, because it is such a clear cut case. There are other cases of joint activity on cultural property issues in Jerusalem, despite the political problems, but as far as I know, none have yet involved the restoration of property. In fact, despite considerable disdain for working with or acknowledging Zionists, moves to restore the books to their rightful owners may in fact lead to significant consciousness raising for Israelis and diaspora supporters who work in cultural institutions. This could also lead to courage to speak out on other issues. There is no logical reason to hold onto the books another than as a tainted war trophy.

Another option is for the issue to be addressed by the International Federation of Library Associations (IFLA), a prestigious international body. There was a strong campaign of condemnation when Bosnia’s National and University Library was burnt down by the Serbian army and many other acts of destruction occurred. It appears to me that the stolen books of Jerusalem Palestinians (or those held in other places in Israel) are an equally valid cause.

As for my copy of Fowler’s, it is going back to George Khamis’ family, and I have now used this story at a Jewish learning event, as a form of consciousness-raising about the reality of the Naqba and the need to engage in restorative justice and I will continue to do so. I will be contacting the National Library in Jerusalem and encouraging others in the library and archive world to also advocate to the Library that they give up what is not theirs.

Note: Thanks to Samah Sabawi for help with an Arabic transcription and to Hannah Mermelstein, Mona Halaby and the family of George Khamis for their cooperation. This article will become part of another study on the politics of archives, and libraries.

- This article appeared in the AJDS Magazine Just Voices 16: Israel / Palestine 1948